Now that our Heritage Lottery Funded project has come to an end, we wanted to write one final post to thank our readers who followed along with the National Union of Women Teachers archive collection. Both the cataloguing and education outreach projects have allowed us to increase accessibility to the collection, and shed a bit more light on these formidable women, determined to level the playing field of gender equality. If you’d like to keep up to date with archive related education resources and blog updates (including classroom lesson plans and activities), head to our new site Archives For All, or the Newsam Library & Archives’ blog Newsam News. Archives get the reputation for being dusty, stuffy places. What collections like the NUWT prove is that archives are anything but useless papers of the past. History’s tendency to repeat itself, as issues of the past continue to present themselves as issues in the present, is no more evident than in collections like the NUWT. The NUWT disbanded in 1961, after achieving equal pay for men and women teachers. Yet, 50+ years on, women continue the fight for equal pay, equal representation, and equal opportunity. During a recent school workshop about life during the First World War, I asked a group of Year 3s, ‘Why are archives important? Why do we bother saving – and looking – at all of this stuff?’ One very clever student raised his hand, and gave the following impassioned explanation:

we need the archives… because we need to learn from our old mistakes so we don’t make them again! – Year 3 student at St Joseph’s in Camden, positioning himself to take my job

On a personal note, this is my last week as the Archive’s Education Coordinator. I have been so lucky to be a part of this team, this archive, and to have had the opportunity to work with such dynamic schools and community members. While working with school pupils (whether they’re Year 2 or university students), the focus has always been on the archives – of course. But alongside that, our objective has been to encourage critical enquiry, investigative skills and above all, to encourage students to question everything both in and outside the history classroom. Go to the source, and then question that source, that issue, that argument. I was recently reading Angela’s Ashes, and was struck by this passage, where Frank describes his teacher. Mr O’Halloran’s words pretty much sum up why we think history education, which fosters all of those above skills, is so important…

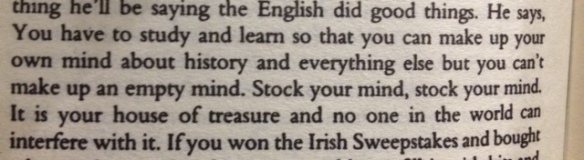

He says, You have to study and learn so that you can make up your own mind about history and everything else but you can’t make up an empty mind. Stock your mind, stock your mind. It is your house of treasure and no one in the world can interfere with it – Frank McCourt, Angela’s Ashes